Hey, Dr. Helen Suh of Tufts University — or anyone else. Shut me up. I’m askin’ for it. Just be specific.

As usual with air pollution junk science, the researchers of this study (Pun study) in the May 24 issue of the American Journal of Epidemiology claim to have found “significantly positive associations” between inhalation of PM2.5 in outdoor air and death from various causes. Here’s the abstract:

And naturally they conclude that:

In this large cohort of US elderly, we provide important new evidence that long-term PM2.5 exposure is significantly related to increased mortality from respiratory disease, lung cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

Is this claim true? Does it even pass the red-face test? I comment you decide.

This is a study of disease in a human population — i.e., epidemiology. As EPA acknowledges in its 2005 risk assessment guidelines, there exist an established set of criteria for evaluating epidemiologic claims.

What are the Bradford Hill criteria? Again from the EPA risk assessment guidelines:

So let’s apply the Bradford Hill factors to the study.

1. Consistency of the Observed Association. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

As to death from respiratory disease, the authors admit that their results are inconsistent with other reported results (see highlighted text):

As to lung cancer, the study authors claim their results are consistent with the conclusions of IARC, but admit they are inconsistent with other published studies:

It is important to note that IARC did no original research and its independence is debatable to say the least.

As to all-cause and CVD-related deaths, the authors also admit inconsistency:

Another possibility for the large-than-expected results is that they are spurious. More importantly, though the independence of the cited studies is debatable. All four studies cited (i.e., references 2, 3, 9 and 21) were conducted by EPA-funded researchers and cronies of study author Helen Suh. More on Suh later.

Conclusion: The study results fail the consistency of association criterion.

2. Strength of the Observed Association. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

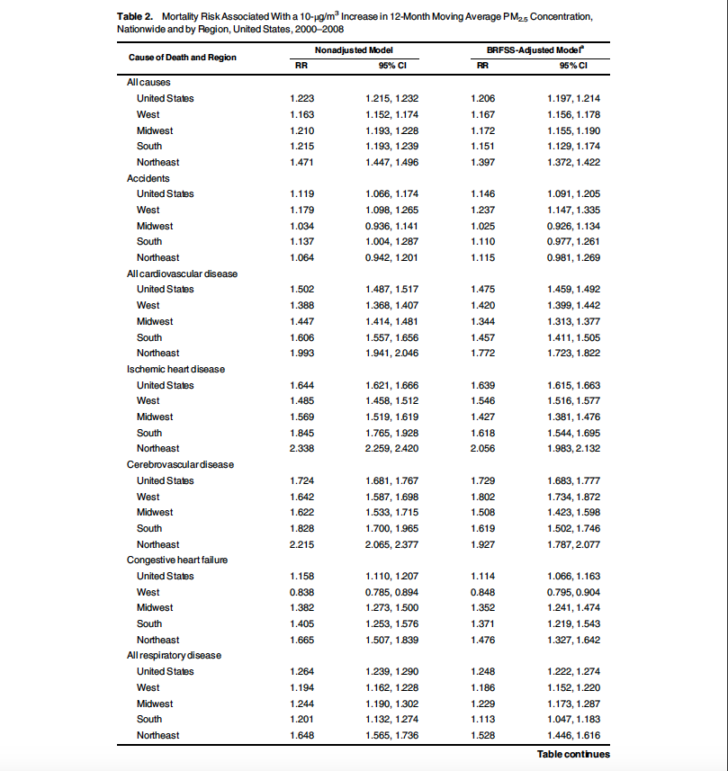

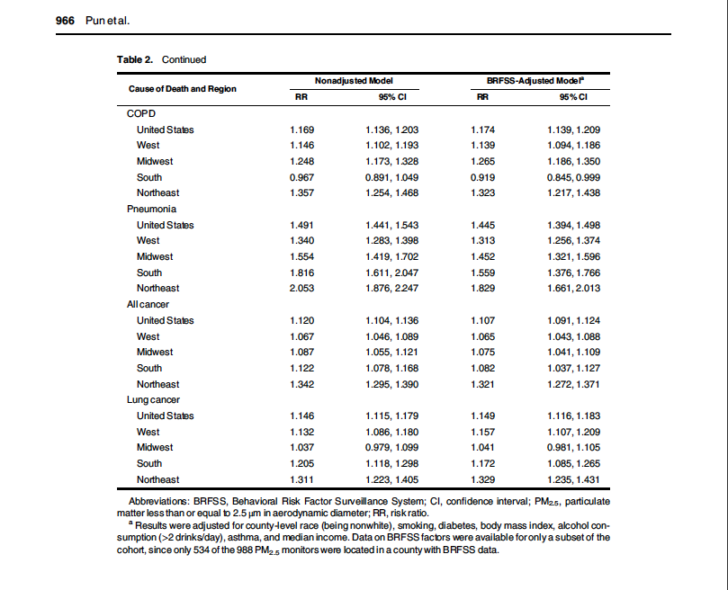

As shown in Table 2, below, of the 55 relative risk results reported, only one is above 2.0 — and that one is 2.056.

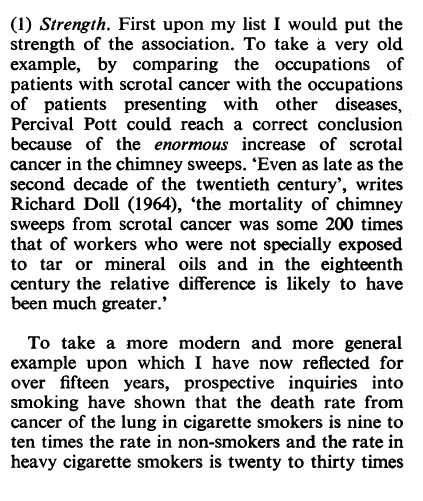

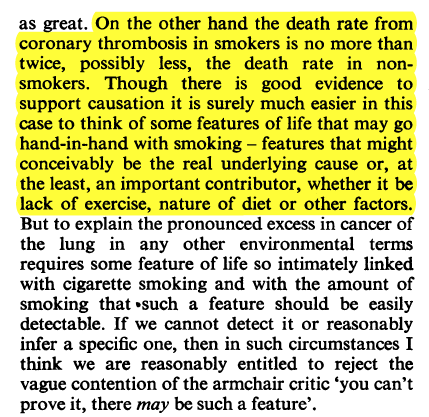

What are we to make of this? Bradford Hill had his own thoughts on strength of association that he explained in his famous 1965 essay in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, entitled “The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation.” This paper also has the honor of presenting Hill’s criteria ultimately adopted by EPA. Hill had little confidence in relative risk estimates below 2.0:

The National Cancer Institute has also dismissed relative risks less than 2.0. From an October 26, 1994 media release issued to bat down an epidemiology study reporting an association between abortion and breast cancer, the NCI stated:

In epidemiologic research, relative risks of less than 2 are considered small and usually difficult to interpret. Such increases may be due to chance, statistical bias or effects of confounding factors that are sometimes not evident.

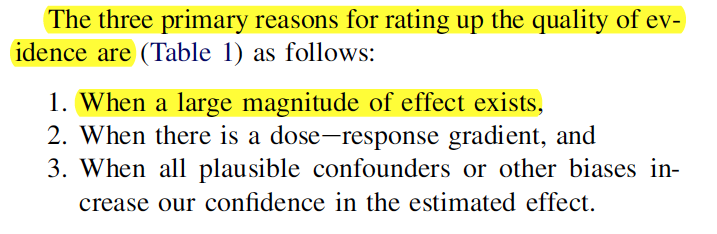

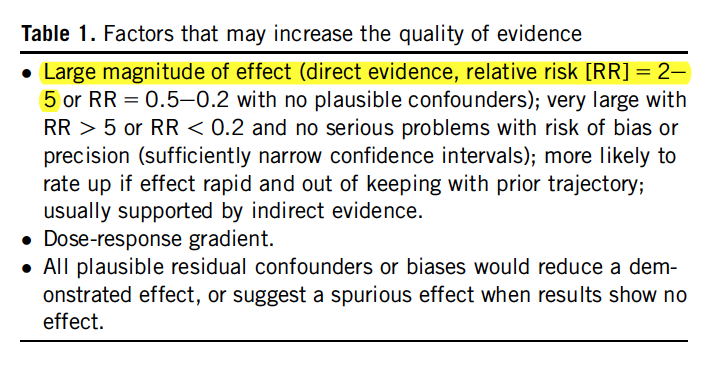

There are also the guidelines for evaluating epidemiologic studies from GRADE (an internationally developed system for interpreting epidemiologic results):

Conclusion: The study results fail the strength of association criterion.

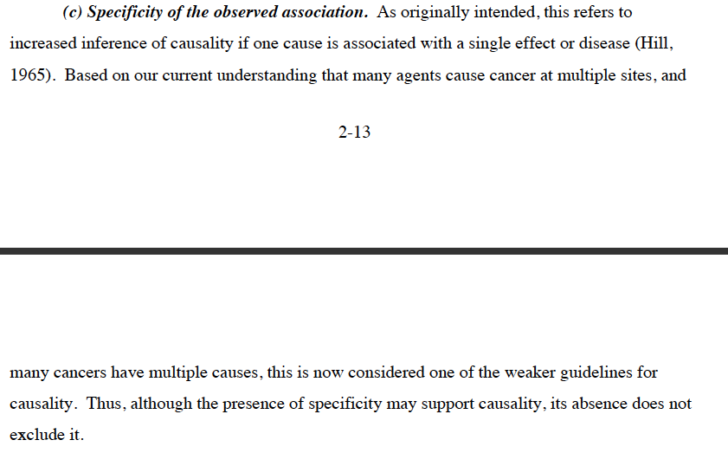

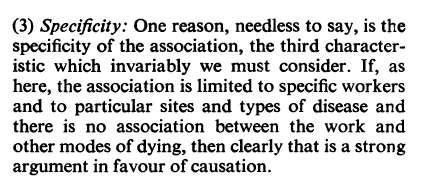

3. Specificity of the Observed Association. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

That is of course EPA’s effort to dismiss this Bradford Hill criterion. Here is what Hill actually wrote:

The Pun study attempts to associate PM2.5 with all deaths, heart disease-related deaths and lung-disease-related deaths. These are all rather broad health endpoints, particularly given the weak relative risks, which are nothing more than weak correlations.

Epidemiology is most useful for identifying high risks of rare disease. Food poisoning incidents, where relative risks can easily reach the 30s and heavy cigarette smoking and lung cancer, where relative risks hit the 20s, are examples of high correlations of comparatively rare events.

In the Pun study, we have weak correlations death associated with a pretty common health endpoint — death. Heart disease-, lung disease- and cancer-related deaths are still pretty common. What about lung cancer? didn’t I just say that lung cancer was a sufficiently specific disease? Yes, I did — but then the relative risk correlation between heavy smoking and lung cancer is in the 20s — not on the (strength of association failure) order of 1.03 to 1.3 as in the Pun study.

An exposure should cause a specific disease — not a common health endpoint affected by many contributory causes and diseases.

It is also important to note that “all cause” deaths is a bogus health endpoint for PM2.5. A death that is accidental, for example, obviously has nothing to do with PM2.5 yet is still counted in the Pun study as in the category of “all cause” deaths.

Conclusion: The study results fail the strength of association criterion.

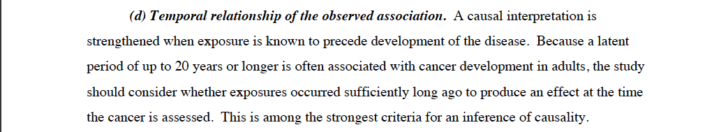

4. Temporal relationship of the observed association. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

Since the health endpoint is death, the claimed PM2.5 associations obviously fit this criterion — at first glance. The problem, however, arises when you consider what EPA says about the timing of PM2.5-associated death.

EPA has made the astounding claim that death from PM2.5 can happen within hours of any inhalation of PM2.5 or over the course of a lifetime of exposure. The excerpt below is from EPA’s 2004 assessment of PM2.5:

So if any inhalation of PM2.5 can kill within hours and given that we are constantly inhaling PM2.5, how would it be possible to show that PM2.5 caused death after long-term exposure? It’s not possible.

So the basic study claim — that long-term exposure to PM2.5 is associated with death — is fatally compromised by the EPA itself.

Conclusion: The study results fail the temporal relationship criterion.

5. Biological gradient (exposure-response relationship). The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

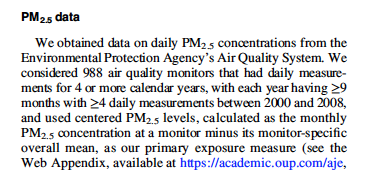

Exposure data is another Achilles heel of PM2.5 studies. The Pun study relies on guesstimates of exposure based on EPA monitors:

Despite the use of air monitors, the reality is that they are a poor proxy of actual PM2.5 exposures.

First, the monitors tend to be located near heavily-travelled roadways. Not many people spend a whole of time in those places inhaling the PM2.5.

Next, and most importantly, people are mainly exposed to PM2.5 in many other ways. Smoking, fireplaces, grills, dust, pollen, pet dander are just a few sources of PM2.5.

A single cigarette (smoked in 5 minutes) can expose one to as much as 200 days worth of the PM2.5 that is contained in average US outdoor air. A single marijuana joint can be worth 800 days of PM2.5.

In the Medicare population analyzed in the Pun study, study subjects were between the ages of 65 to 120 years during the period 2000-2008. As many as 50% of men and 33% of women in this generation smoked cigarettes. Everyone was exposed to secondhand smoke. Then there are other lifestyle and occupational exposure to smoke, dust, pollen and mold. So lifetime PM2.5 exposures are off the charts. PM2.5 exposures from outdoor air are unknown and likely inconsequential.

Conclusion: The study results fail the biological gradient criterion.

6. Biological plausibility. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

The Pun study is strictly a statistical study and sheds no light on the biological plausibility of whether PM2.5 can cause death. EPA has, in fact, admitted to a federal court in litigation with me that its epidemiologic studies to not prove that PM2.5 causes death, as follows:

Although there has been much speculation, no one has any idea whatsoever of how inhalation of PM2.5 might cause death.

There are two primary means of studying biological plausibility — animal toxicology and human clinical research.

As to animal toxicology study, no animal exposed to (massive amounts of) PM2.5 has ever died because of the PM2.5 exposure.

As to clinical research,most of which has been funded and or conducted by EPA itself, no harm, let alone death, has ever been caused by PM2.5.

Conclusion: The study results fail the biological plausibility criterion.

7. Coherence. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

Here’s what Hill wrote about coherence in his essay:

EPA essentially invented the notion that PM2.5 killed in the mid-1990s. Until then, no one imagined this to be some because it is not.

For example, in all three fatal air pollution incidents of the 20th century [Meuse Valley, Belgium (1930), Donora Pennsylvania (1948), London (1952], PM2.5 was not blamed because everyone knew from real-life experience that PM2.5 from combustion (i.e., carbon particles) are innocuous. You can read more about this in Scare Pollution: Why and How to Fix the EPA, pp. 199-208).

Hill mentions his fondness for the histopathological evidence on smoking. In the case of the deaths at Donora, autopsies performed there indicated that acidic aerosols — not PM2.5 — were the culprit.

The smoking epidemiology also illustrates the incoherence of the notion that PM2.5 kills. Smokers inhale vastly greater amounts of PM2.5 than nonsmokers. Not only does smoking not kill within hours of smoking but a smoker can inhale about 3,500 times more PM2.5 than a nonsmoker and have the same life expectancy (more on this below). As discussed above, seriously sick people needing oxygen can smoke (huge amounts of PM2.5) for years.

EPA’s adoption of the Hill criteria mentions animal bioassays. But no animal have ever died in a PM2.5 bioassay despite being exposed to immense amounts of PM2.5.

Conclusion: The study results fail the coherence criterion.

8. Experimental evidence from (from human populations). The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is:

Hill’s essay explains this criterion as follows:

So we have several of these “natural” experiments.

The first and foremost is notoriously bad air quality in places like China and India, where the worst air can have PM2.5 levels 100 time greater than average US air. Are there any observed or confirmed PM2.5-related deaths related to this atrocious air pollution? No. I’d give you a citation, but I can’t cite what isn’t reported.

If we are to believe Chinese vital statistics, the life expectancy of Beijing residents is greater than those of Washington, DC residents even though Beijing air averages 10 times more PM2.5 than Washington, DC.

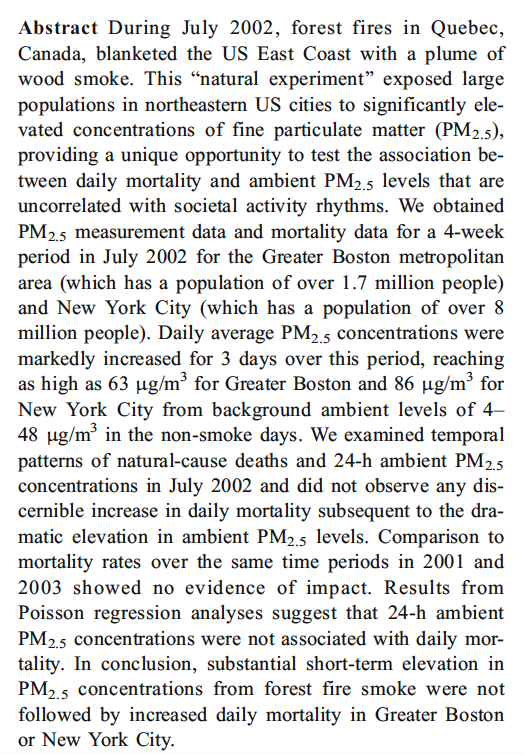

Forest forest fires also are a great “natural experiment.” They should leave greater death tolls in their wake from the PM2.5. But they don’t. Here’s an example:

There is no “natural experiment” or other human experimentation, including EPA’s human clinical studies, that supports the notion that PM2.5 kills.

Conclusion: The study results fail the experimental evidence criterion.

9. Analogy. The EPA-adopted Bradford Hill criterion is (SAR = structure-activity relationship):

Hill’s comment on this was:

As there is no known mechanism by which PM2.5 could possibly cause death, it’s impossible to consider analogs.

Conclusion: This criterion is irrelevant.

So the Pun study satisfies NONE of the Hill criteria for inferring causation from epidemiology studies.

But there are a couple more shortcomings of the Pun study that I have not already discussed in above.

- Actual causes of death unknown in study population. The study population consists of the Medicare records of 18 million people. Available data included: date of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, zip code of residence and survival (presumably date of death). Note that cause of death is missing from the data fields. To replace the lack of cause of death, the researchers estimated the distribution of causes of deaths. So we really don’t know what any of these people died from. This constrasts with our California study (reporting no association between PM2.5 and death) as the 2 million death certficates we used did contain cause of death.

- Cherry -picked study subjects? Though there were 52.9 million eligible Medicare enrollees during the period of the study, the study only included 18.9 million (36%) of them. No explanation is provided for this culling. Were the 18.9 million selected to provide the best possible results? Inquiring minds would like an answer. What would the results be if all 52.9 million (or as many as there are data for) are included in the analysis. As a comparison, our California study includes about 94% of deaths that occurred in California during 2000-2012. The only California deaths not included in the study were those in areas where the air is so clean, daily PM2.5 monitoring was not done.

- Allusion of statistical strength. The study’s relative risks all report pretty tight confidence intervals — normally a science of data consistence and quality. But these tight confidence intervals are actually created by virtue of the fact that the study involved 18.9 million subjects. A very large “n”, tends to produce very definite results. This des not mean the correlations are any good. It just gives them the appearance of it.

- Research by conflicted EPA crony. Helen Suh, the researcher who organized this study, is a long time EPA crony. She’s garnered over $16 million in EPA grants for her university and has served on the EPA CASAC boards where EPA grantees get to review and rubberstamp their own work in furtherance of the EPA regulatory agenda and more EPA grants.

So here’s the summary: No one knows what the PM2.5 exposure was for any study subject. No one knows the cause of death of any study subject. Study subjects were cherry-picked to produce a purely statistical study that has no physical, medical or scientific support. Yet the study is offered as evidence that PM2.5 kills. Kills what? Researcher integrity?