By Steve Milloy

JunkScience.com, March 2019

Background: What is an “endocrine disruptor”?

An endocrine disruptor (also called an “environmental estrogen”) is supposedly any one of a variety of chemicals that, at extremely low-level exposures, well below those considered safe by EPA and other regulatory authorities, disrupt the human or animal hormonal system to cause diseases or conditions such as development defects, infertility, obesity, Alzheimer’s, autism, cancer and others.

A key argument of those advancing this thesis is that standard laboratory tests fail to pick up on these hazards because the harmful effects of the endocrine disrupting chemicals or compounds, often called EDCs for short, vanish as the dose increases (though they may increase again as the dose is raised even higher). In other words, EDC advocates discard the proven toxicological principle that “the dose makes the poison,” i.e. that toxic effects of a substance increase as dose or exposure to the substance increases. In fact, they turn it on its head, saying that for this special class of chemicals, the reverse is true.

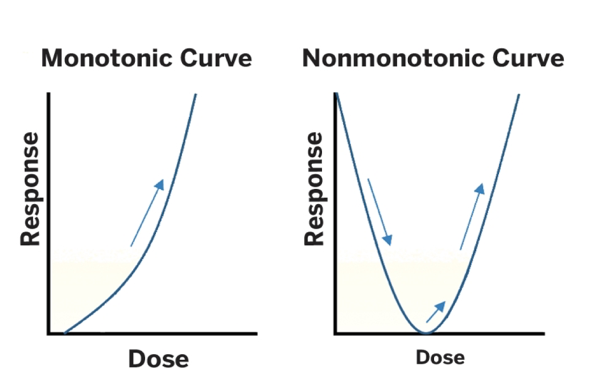

This contrast is illustrated in the graphs below. The standard dose response — seen in all toxicology to this point – is called a “monotonic” curve, meaning it is always moving in one direction, up or down. EDC advocates say that these special compounds produce a U-shaped or “non-monotonic” dose-response curve.(1)

It is important to note that the existence of the non-monotonic dose response which is key to the endocrine disrupter scare and is which is loudly advocated by a small group of activist scientists remains only a hypothesis and has never been scientifically validated. Twenty-two years after the EDC thesis was first advanced, not a single chemical has even been demonstrated to act non-monotonically that is, to cause harm at low doses but not at higher ones.

Useful concepts

Activists often (intentionally) try to confuse the public about endocrine disruptors on two key issues:

- Low vs. high exposures. The endocrine disruptor scare is exclusively about low-dose or low-level exposures to chemicals in the environment. Activists often throw into the mix examples of harm caused by high-level exposures to chemicals.

- Harm vs. mere effects. Activists often tout the results of studies that report chemicals caused some biological effect to occur vs. actual harm. Prior to being dubbed “endocrine disruptors” by the activists, substances that act like hormones to produce effects at small doses but no harms, were referred to in a more neutral terms as “endocrine modulators” by scientists.

The endocrine disruptor scare is about actual harm caused by low-level exposures to chemicals in the environment. More on these points below.

Dose makes the poison Toxicology is the study of poisons. A basic principle of toxicology is “the dose makes the poison.” This means that any substance can produce poisonous, toxic or harmful effects if one is exposed to enough of it. Here are three variations of this principle.

- Example: Ingesting too much arsenic can be fatal. Nonetheless, some arsenic can be safely ingested without any toxic effect.

- Example: While we cannot live without drinking water, drinking too much water can cause death by upsetting the body’s electrolyte balance and fatally disturbing brain function.

- Example: While inhaling too much carbon monoxide can cause death, the human body naturally produces a necessary but small amount of carbon monoxide.

There is no example in toxicology where any non-zero exposure to a substance causes harm. Every substance has a safe or no-effect exposure level.

Distinguishing between harmless biological effects and harmful or adverse effects. A related principle to “the dose makes the poison” is the distinction between mere biological effects and actual harm following exposure to a substance. Mere exposure to a substance does not necessarily cause a harmful or toxic effect (i.e., the dose makes the poison). But all exposures cause biological effects. Drinking water, for example, causes biological effects, ranging from beneficial (if you are dehydrated), neutral (in case of normal hydration) or harmful (in case of overhydration). The mere occurrence of an effect does not imply that the effect was harmful or adverse.

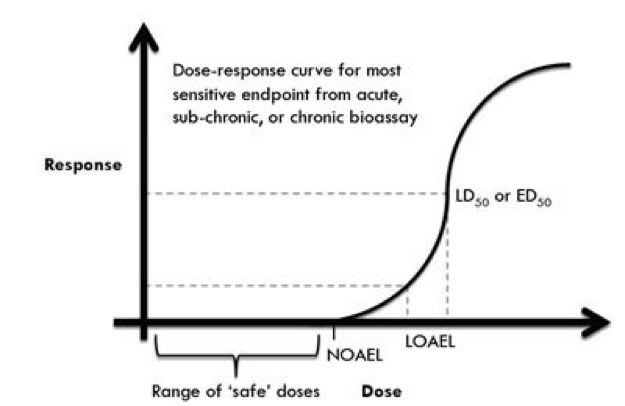

Dose-response. The relationship between exposures (or doses) and effects is called the “dose-response” relationship. It may be represented graphically by a dose-response graph or “curve” (See below). This curve illustrates some of the aforementioned concepts. The ‘no-observed-adverse-effect-level’ or NOAEL is the highest dose at which no biological effect is observed. The lowest-observed-adverse-effect is a point or range at which biological effects begin to be observed. (The LD50 is the point at which half the lab animals are outright killed by the dose it is not relevant to this discussion.)

It will be seen later that the “low-dose hypothesis” area of the endocrine disruptor scare involves doses at the NOAEL and below — the “hypothesis” being that any non-zero exposure to an endocrine disruptor can cause an adverse effect. The low-dose hypothesis, then, is contrary to everything that is has been observed in standard toxicology.

Natural versus synthetic endocrine modulators

Many natural substances may also have hormone-like effects. Phytoestrogens, for example, are not produced by our endocrine system but are present in many of the vegetables and fruits that make up a healthy diet. Below is a list of some phytoestrogens.(2)(3)

One of the problems with the EDC scare as advanced by the activists is that they almost exclusively focus on made-made, synthetic chemicals, even though our exposure to so-called EDCs from natural sources, which are known to be safe and even healthy – are massively higher. Stephen Safe, a toxicologist at Texas A&M University, points out that “the total hormonal activity of the synthetic modulators we receive from industrial activity is 40 million times lower than that from the natural components of foods we eat.”(4) [Italics added]

Bisphenol A, or BPA, a substance used to harden plastics, and phthalates, substances that make them more flexible, have become a prime focus of EDC claims and have been removed from many household products as a result. But according to researchers at King’s College in the United Kingdom, their tests on laboratory animals showed that one natural estrogen found in plants “is 10 to 100 times as potent as bisphenol A. They also found that three different phthalates — the chemicals that caused the British dairy panic — produced no hormonal effects whatsoever.”(5)

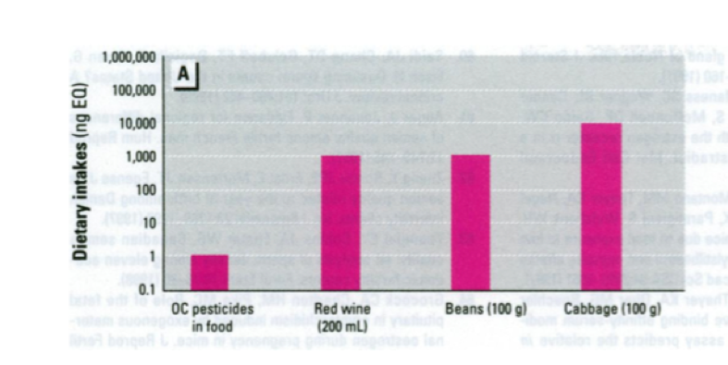

Red wine, beans and cabbage, for example, range from 1,000 to 10,000 times more active as endocrine modulators than organochlorine pesticide residues found in food.(6) The chart, below, shows that eating 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of cabbage provides an estrogen exposure 10,000 times greater than that from typical daily consumption of foods with organochlorine pesticide residues.

Origin the endocrine disruptor scare: Rise and fall of the cancer hypothesis

Rachel Carson dramatically alleged various harms to human health and the environment caused by industrial chemicals in her 1962 book “Silent Spring.”

In 1965, the Johnson administration expressed this concern by the creation of the Department of Environmental Health Sciences (DHES) housed within the National Institute of Health (NIH). In 1969, the DEHS was converted into an “institute” within the NIH called the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences.

Also in 1965, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). By 1970, IARC established its “Monogram Program” to evaluate chemicals and other agents for carcinogenic potential.

In 1970, President Nixon combined a number of ongoing federal environmental regulatory efforts occurring in separate federal agencies into one Environmental Protection Agency. One of EPA’s first major acts was to ban DDT, the insecticide of focus in Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring.” DDT was banned despite an EPA administrative law judge concluding after seven months of hearings and 9,000 pages of testimony that there was no evidence that DDT had harmed humans or wildlife. The EPA administrator making the decision, William Ruckelshaus, did not attend a single moment of the DDT hearings and, according to his staff, did not even read the transcript. Later, Ruckelshaus became fundraiser for the Environmental Defense Fund, the activist group that led the charge to get DDT banned.

In the early 1970s, the Nixon administration launched its “war on cancer,” which in turn led to federal regulatory focus on the possibility that chemicals in the environment caused cancer. By 1974, NIEHS established a program to study the links between chemicals in the environment and cancer. In 1976, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was enacted to enable EPA to regulate the use of chemicals. One of the driving forces behind TSCA was concern that chemicals in the environment caused cancer.

In 1978, the National Toxicology Program was formed within NIEHS to coordinate and lead toxicology programs in the federal government. NTP was made a permanent program in 1981.

So by the early 1980s, EPA, NIEHS/NTP and IARC were extensively involved in toxicology, with particular focus on trying to link chemicals in the environment to cancer.

But even by the time of TSCA (1976), scientists knew that it would be very difficult, if not practically impossible, to link chemicals in the environment or consumer products with cancer.

Absent strong epidemiological evidence, characterizations of a substance’s carcinogenic potential had to be based on laboratory animal tests that are very controversial and of unclear if not dubious relevance to humans.(7)

In 1990, molecular biologist Bruce Ames reported that naturally occurring chemicals (like those in raw and cooked food) are as likely to test positive for carcinogenicity in laboratory tests as synthetic chemicals (like pesticides). Since humans are exposed to much greater levels of the natural chemicals without apparent effect, exposure to the synthetic chemicals is not likely to be of any significance.(8)

A 1999 study, for example, reported that 85 percent of the chemicals and agents studied by NTP over the years exhibited either carcinogenic or anti-carcinogenic activity in laboratory animal tests.(9) This result is difficult if not impossible to reconcile with real-world exposures to chemicals and disease incidence.

Origin the endocrine disruptor scare: Rise of ‘endocrine disruptor’ controversy

The failure of the chemicals-cause-cancer hypothesis prompted activists to search for new ways to link industrial chemicals with adverse health and environmental consequences.

After a career as pharmacist, Theo Colborn earned a PhD in zoology in 1985 at age 58. She studied the effects of chemicals in the environment on Great Lakes wildlife. Colborn began working at the environmental activist group World Wildlife Fund in 1987 and then with the environmental activist sponsor, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, in 1990.(10)

In 1991, Colborn convened like-minded individuals under the auspices of the W. Alton Jones Foundation in the first of a series of conferences in Racine, WI that came to be known as “Wingspread.”(11) During that meeting, the term “endocrine disruption” was coined.(12) The Wingspread “Consensus Statement” concluded that chemicals in the environment, even at low doses, “can cause alterations of the developing immune system” such that “the potential exists for widespread immunotoxicity in humans and wildlife species because of the worldwide lack of appropriate standards.”(13)

It should be noted that, to the extent the issue of chemicals in the environment had been discussed among scientists prior to the first Wingspread conference, they were referred to more benignly as “endocrine modulators.” The Wingspread re-branding of potential “endocrine modulators” as “endocrine disruptors” was clearly meant produce alarm among an ignorant public.

On August 23 1994, the endocrine disruptor scare was reported in the New York Times in an article titled “Pesticides May Leave Legacy of Hormonal Chaos.” Referring to some wildlife populations, Colborn stated, “I’d say we are on a fast track to extinction… You would expect the same thing to happen to human populations.” A toxicologist from the American Council on Science and Health noted, “We suspect there is a lot of baloney here. On the other hand, to develop the hard science to refute it is going to be a formidable task.” The New York Times article concluded with “But for now the science simply does not know enough to say just how serious a threat they pose.” The article foreshadowed some of the endocrine disruptor claims to come including synergistic effects of combinations of endocrine disruptors, sperm count decline, endocrine disruptors in plastics and the low dose controversy.

It’s worthwhile to note this excerpt from the New York Times article:

But perhaps the greatest fears expressed about the effects of endocrine disruptors on humans have to do with sex and reproduction. The case of the Taiwanese boys may reflect the effects of high doses. But more insidious and threatening in the long run, say Dr. Colborn and others, may be the subtle effects of low doses in the womb. As was shown with the synthetic hormone DES, prescribed from 1948 to 1971 to prevent miscarriages, exposure of the fetus to endocrine disruptors can cause reproductive problems that do not become evident until many years later.

DES was a medication and so at best, an example of a high-dose effect consistent with traditional toxicology (i.e., the dose makes the poison). “DES is not only a potent estrogen, but it was administered at relatively high doses… In contrast synthetic environmental endocrine-disrupting compounds tend to be weakly active,” observed toxicologist Stephen Safe.(14)

In July 1995, the National Research Council (NRC) of the National Academy of Sciences formed a Committee on Hormonally Active Agents in the Environment to “critically review the literature on hormone-related toxicants in the literature…”(15) The Committee was formed by the Clinton administration under contracts from the EPA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Department of Interior.(16)

The precise origin of this Committee is unknown but one can easily imagine that it was quietly lobbied for by endocrine disruptor advocates. The Executive Summary section of the report indicates it was “driven by considerable public interest.” The report’s Introduction section states, “In recent years, there has been increasing concern regarding [potential adverse human health effects of various environmental contaminants designated by some scientists as “endocrine disruptors” (Thomas and Colborn 1992; Colborn et al. 1993 ).”(17, 18) However, Theo Colborn’s name only appears once, for example, in the New York Times prior to the announcement of the formation of the NRC committee and that was in a letter to the editor.(19) While there are various other media stories quoting Colborn in national and local media between 1989 and 1995, it is not at all clear that this supports the notion of “considerable public interest” in or “increasing concern” for endocrine disruptors.

In March 1996, the book “Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival A Scientific Detective Story” was published with Colborn as a co-author along with journalist Dianne Dumanoski and then-director of the W. Alton Jones Foundation and Wingspread Consensus Statement signatory, John Peterson Myers.

In its March 19, 1996 coverage of “Our Stolen Future,” the New York Times reported (as excerpted):

In a warning supported by allies who include Robert Redford and Vice President Al Gore, some environmentalists are asserting that humans and wildlife are facing a new and serious threat from synthetic chemicals…

But issues like declining sperm counts are a matter of heated dispute among experts…

But its message is controversial. Although some biologists agree that there is reason for concern about these chemicals, especially to certain populations of fish and birds, many others say there is no factual basis for the book’s alarms, several of which have been refuted by careful studies…

In a foreword, Mr. Gore compares it with “Silent Spring,” Rachel Carson’s classic 1962 book that set off a movement to ban DDT and other pesticides. He describes the new book as “critically important”…

But several leading scientists view such positions as premature at best. They say that the case for ridding the world of these chemicals seems fueled more by hyperbole than facts and that many of the claims of demonstrable harm, when examined, turn out to be a house of cards.

These scientists say they are not arbitrarily dismissing fears that trace amounts of synthetic chemicals might injure people and wildlife. But, they say, there is a difference between a hypothesis and convincing evidence.

“It’s hypothesis masked as fact,” said Michael A. Gallo, a professor of toxicology at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

This assessment was also shared by Dr. Bruce Ames, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California at Berkeley. “It’s a political movement and it’s based on lousy science,” said Dr. Ames, who was a member of a National Academy of Sciences panel that recently reported that pesticide residues in food were not an important cause of cancer.

Scientists agree that certain synthetic chemicals may mimic reproductive hormones. And, they say, there is no doubt that some of those chemicals, at certain times and places, have reached levels that adversely affect wildlife.

But, the question is, what, if any are the effects of minute amounts of these chemicals on humans? And that is where environmentalists like Dr. Colborn part company with many scientists.

One issue, scientists say, is that the amounts of the synthetic chemicals are so minuscule that they might be dwarfed by naturally occurring hormones in plants that have the same effects. Dr. Stephen Safe, a professor of toxicology at Texas A & M University, has calculated that synthetic chemicals contribute less than one one-thousandth of 1 percent of the amount of estrogenlike compounds that people consume in their diets…

Another possibility raised in the book is that endocrine-disrupting chemicals can cause parents to neglect or abuse their children.

“What about the breakdown of the family and frequent reports of child abuse and neglect?” the authors wrote. “If scientists have found evidence of careless parenting in contaminated bird colonies, do these chemicals have any role in similar phenomena among human parents? Reacting to reports of growing neglect and violence against children by their parents, some commentators have ventured that there must be something wrong with these people, some basic instincts seem to be missing.”

But Dr. Zahm of the cancer institute dismissed the argument that endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the environment could cause such a variety of ills as “a leap — in the quantum category.”

“We shouldn’t go beyond what our data show,” she added.

In June 1996, just months after the widely publicized release of “Our Stolen Future,” a study was published by Tulane University researchers in the journal Science reporting that combinations of pesticides and other chemicals in the environment could be as much as 1,500 times more potent as so-called “endocrine disruptors” than the individual chemicals.(20) In an unusual move, Science also editorialized favorably about the new study.

In reaction to the Tulane study, EPA administrator Carol Browner stated, “The new study is the strongest evidence to date that combinations of estrogenic chemicals may be potent enough to significantly increase the risk of breast cancer, prostate cancer, birth defects and other major health concerns.” The head of EPA’s Office of Pesticides and Toxic Chemicals said, “I was astounded by the findings. I just can’t remember a time where I’ve seen data so persuasive… The results are very clean looking.”

In July 1996, Congress inscribed the notion of endocrine disruptors into federal law. The Food Quality Protection Act ordered EPA to set up a program for screening pesticides and other industrial chemicals for their ability to act as endocrine disruptors.(21) The legislative history indicates reliance on the Tulane study.(22)

The EPA program for screen endocrine disruptors is called the Endocrine Disruptor Screen Program (EDSP). As of May 2011, the EDSP had “not determined whether any chemical is a potential endocrine disruptor.” (23)

As of the present, EPA has evaluated 52 chemicals and reported the following results: evaluated based on Tier 1 screening, intended to identify whether a substance has the potential to have hormonal activity:(24)

- There was no evidence for potential interaction with any of the endocrine pathways for 20 chemicals.

- 14 chemicals that showed potential interaction with one or more pathways, but EPA determined it enough information to conclude that they do not pose risks.

- Of the remaining 18 chemicals, all 18 showed potential interaction with the thyroid pathway, 17 of them with the androgen pathway, and 14 also potentially interacted with the estrogen pathway. These chemicals are moving on to Tier 2 screening, intended to ascertain their effects in real-world systems.(25)

The Tulane Study is retracted because of scientific misconduct

To recap, the endocrine disruptor scare was launched for public consumption by “Our Stolen Future” in March 1996. About ten weeks later, a new study in a prestigious journal appeared to lend credibility to concerns about endocrine disruptors. One month after the study, the notion of endocrine disruptors had been enshrined in federal law.

By November 1996, four laboratories had tried but failed to replicate the Tulane findings – a highly unusual outcome in the controlled setting of laboratory research. In January 1997, Science printed a letter from scientists NIEHS, Texas A&M University and Duke University reporting the Tulane results could not be replicated. A month later, the highly regarded international science journal Nature published results from British researchers who could not replicate the Tulane findings.(26)

The Tulane researchers initially responded to critics by claiming special conditions in their laboratory. But “special conditions” are the stuff of magic, not science. Scientific findings are supposed to describe the world in general, not some special place.

In July 1997, the Tulane team finally threw in the towel and retracted their study. In a letter to Science they wrote, “We . . . have not been able to replicate our initial results . . . (and) others have been unable to reproduce the results we reported.”(27)

In 1999, the NRC Committee on Hormonally Active Agents in the Environment (the mysteriously formed Committee established in July 1995) issued its eponymous report. The Committee failed to confirm the hypothesis of “Our Stolen Future,” concluded that, “Although there is evidence of harmful health and ecological effects associated with exposure to high doses of chemicals known as hormonally active agents – or endocrine disruptors – little is understood about the harm posed by exposure to the substances at low concentrations, such as those that typically exist in the environment, says a new report from a National Research Council committee.” [Emphasis added]

Author’s Comment: The phrase “little is understood” is political/weasel language meant as a compromise between reality (i.e., there is no evidence that endocrine disruption occurs) and the needs/goals/threats of activists and their researcher allies (i.e., we’ll scream, bloody murder if you embarrass us by stating reality). This is obviously politics, not science.

The NRC Committee confirmed that the traditional dose-response relationship still held true for so-called “endocrine disruptors” i.e., harm is only observed at high doses/exposures. This conclusion, however, would just force activists to resort to claims about low doses/exposures causing harm (discussed below).

In October 2001, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Research Integrity determined that the Tulane study results were produced by scientific misconduct: “Dr. Arnold committed scientific misconduct by intentionally falsifying the research results reported in Table 3 of a paper published in the journal Science and by providing falsified and fabricated materials to investigating officials at Tulane University in response to a request for original data to support the research results and conclusions reported in the Science paper. In addition, [the Public Health Service] finds that there is no original data or other corroborating evidence to support the research results and conclusions reported in the Science paper as a whole.”(28)

Theo Colborn favorably cited two of Arnold’s co-authors on the retracted Science paper, John McLachlan and Louis Guillette, in “Our Stolen Future.” Arnold, McLachlan and Guillette are also cited numerous times in the 1999 NRC report as are other of Arnold’s co-authors.

The Rise of the Low Dose Hypothesis

Recall that National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) traces its roots back to the 1960s pesticide scare launched by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book “Silent Spring.” NIEHS has since been a hotbed for activist-researchers. Not only does NIEHS conduct its own “research”, it provides grants to extramural researchers. NIEHS also publishes its own journal, Environmental Health Perspectives, to spotlight research its activist editors desire. NIEHS has tried to come to the rescue of the endocrine disruptor scare at least twice in 2000 (low dose hypothesis conference, discussed below) and 2007 (consensus statement on BPA, discussed later).

After the NRC report failed to endorse the endocrine disruptor hypothesis and, by extension, the basis of the legally-mandated EPA Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program, the EPA requested the NIEHS and NTP to convene a group to evaluate “the scientific evidence on reported low-dose effects and dose-response relationships for endocrine disrupting chemicals in mammalian species that pertain to assessments of effects on human health.” The “review” of the Endocrine Disruptors Low Dose Peer Review Panel occurred on October 10-12, 2000.(29)

Keeping in mind the previously discussed distinction between mere biological effects and harms caused by exposure to chemicals, the two key conclusions of the NIEHS Panel to have great significance going forward were:

- “Low-dose effects… were demonstrated in laboratory animals exposed to certain endocrine agents.”

- Several studies provide credible evidence for low-dose effects of bisphenol A (BPA).

An NIEHS Panel conclusion that was equally significant but soft-pedaled was that, “The toxicological significance of many of these findings has not been determined.” The importance of this conclusion is a recognition that just because a chemical exposure produces a detectable/discernible biological effect, that does not mean that the biological effect is necessarily harmful.”

The NIEHS Panel’s low-dose and BPA conclusions were largely based on the research of University of Missouri professor and “Our Stolen Future” hero Frederick vom Saal.

Vom Saal claimed his experiments on laboratory mice showed that very low doses of some chemicals — thousands of times lower than then-extant safety standards — increased prostate weight in male mice and advanced puberty in female mice. But no other laboratory had been able to reproduce vom Saal’s work. Traditionally, reproducibility of experiments is necessary before results may be considered “scientific.”

Vom Saal all but guaranteed that his work will never be reproduced. His experiments involved a unique strain of mice that he inbred in his laboratory for about 20 years. His mice were genetically unique. When the mice stopped producing the results he wanted, he killed them. Without the same strain of mouse, vom Saal’s experiments could not be reproduced by others and his work could not be thoroughly evaluated.

When the NIEHS Panel asked the public to nominate studies to be reviewed, they had set clear ground rules that a study’s raw data had to be submitted to the panel as a prerequisite for the study to be considered. The NIEHS Panel wanted to subject the data from these studies to “independent analysis.”

Vom Saal’s studies were nominated, but he refused to submit his data. Inexplicably, the panel changed the ground rules to include vom Saal’s studies anyway.

The BPA controversy

Though BPA was mentioned in “Our Stolen Future,” it wasn’t until the 2000s that it became the poster child of the endocrine disruptor scare.

The 2000s witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of studies published on BPA. In 1990, the year before the first Wingspread conference, only 70 papers on BPA were published in the scientific literature that year. For 2001, the number published had increased to 294. By 2014, there had been over 800 studies on BPA published in the literature.(30) It is important to note that the volume of studies being published was caused by the vast amounts of federal grant money being dispensed to BPA researchers rather than any important results they were reporting.

By the mid-2000s, legislation and regulatory action against BPA began to crop up on state, city and foreign government levels. This activity occurred among conflicting government reports on BPA. Some highlights include the following:

- In 2005, California became the first state to try to ban BPA from consumer products.(31) That bill having failed, San Francisco tried to ban BPA in 2006.(32)

- None of this activity was slowed one bit by the 2007 report from the National Institute of Health Center for the Evaluation of risks to Reproduction that concluded that BPA had little to no effect on human health.(33)

- In 2007, a so-called “expert panel” of NIEHS scientists, grantees, and collaborators issued the Chapel Hill consensus statement on potential health effects of exposure to BPA. The panel concluded that current levels of BPA in people are higher than what is needed to cause harm in animals, and that the safe dose established by the EPA needs to be lowered.(34) Notable panel members included Fred vom Saal (spotlighted in “Our Stolen Future” and excused from providing data to 2000 NIEHS low dose panel), Linda Birnbaum (current head of NIEHS), Louis Guillette (spotlighted in “Our Stolen Future” and co-author of retracted Tulane study), John McLachlan (spotlighted in “Our Stolen Future” and co-author of retracted Tulane study), John Peterson Myers (co-author of “Our Stolen Future”) and Ana Soto (“Spotlighted in Our Stolen Future”).

- In 2010, Health Canada declared BPA to be a “toxic substance.”(35) But a WHO panel concluded the Health Canada action was premature.(36) In late 2010, however, the European Commission voted to ban BPA in baby bottles starting in 2011.(37) In October 2011, US industry announced BPA was no longer present in sippy bottles.(38) The FDA formalized the sippy bottle ban in July 2012.(39) In December 2012, Suffolk County, NY banned BPA from cash register receipts.(40)

- In December 2014, the FDA reaffirmed that BPA is safe in food containers and cans.(41) In January 2015, the European Food Safe Authority concurred that BPA was unlikely to pose a risk to consumers.(42)

- In April 2016, California announced it would require labeling of food container with BPA.(43)

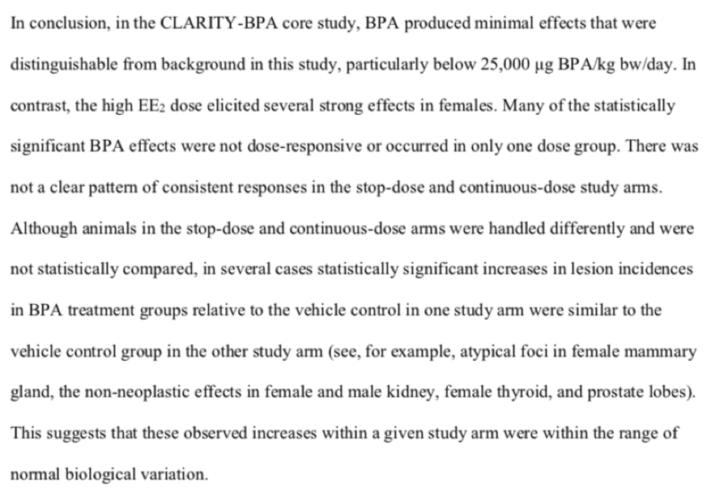

- In February 2018, the NIH and FDA released a report that concluded even “high” doses of BPA found in water bottles and other products had only “minimal effects.” And those effects could have been a coincidence.(44)

CLARITY on BPA

In 2012, NIEHS and the FDA started an “multipronged, consortium-based approach to optimize BPA-focused research investments to more effectively address data gaps and inform decision making.”(45)

CLARITY-BPA has two components:(46)

The draft Core Study was released for public comment in February 2018. The draft conclusion — that there are no discernible effects of BPA — is below:

In addition to the CORE study, 13 academic researchers received about $8 million in funding to participate in CLARITY. To avoid researcher bias, the academic researchers received coded animals so they would not know which BPA dose group any animal came from. They were then required to upload their raw data to a government database before the code could be broken and dose group details were disclosed to them. After disclosure the researchers were able to analyze their data.

While all thirteen academic researchers have completed their work, the results from only five of the thirteen researchers have been published since 2015. Consistent with the CORE study, no-to-minimal effects were reported in those studies.

Below are the 13 academic researchers, their areas of research for CLARITY. The bolded academics have not published their results as of February 2019.

- Obstructive voiding disorder – Fred vom Saal, University of Missouri

- Testes function – Kim Boekelheide, Brown University

- Erectile dysfunction – Nestor Gonzalez-Cadavid, UCLA

- Ovarian dysfunction and abnormal hormone levels – Jodi Flaws, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Neurobehavioral effects – Heather Patisaul, North Carolina State University; Cheryl Rosenfeld, University of Missouri.

- Immune dysfunction – Norbert Kaminski, Michigan State University

- Metabolic disease – Andrew Greenberg and Beverly Rubin, Tufts University

- Obesity – Nira Ben-Jonathan, University of Cincinnati

- Cardiovascular effects – Scott Belcher, University of Cincinnati

- Thyroid effects on brain and intestine – R. Thomas Zoeller, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

- Mammary – Ana Soto, Tufts University

- Uterus – Shuk Mei Ho, University of Cincinnati

- Prostate – Gail Prins, University of Illinois at Chicago

The eight researchers who have not published their results have been critics of BPA in the past and should be motivated to publish their results if they indicated that BPA was not safe. But so far – just silence. It should be noted that academic researchers Fred vom Saal and Ana Soto were originally featured in “Our Stolen Future.”

The Grantee Studies data is scheduled to be released in August 2018. The final BPA-CLARITY report is scheduled to be released in August 2019.

The Sperm Count Controversy

In 1992, Danish research Niels Skakkebaek reported, “There has been a genuine decline in semen quality over the past 50 years. As male fertility is to some extent correlated with sperm count the results may reflect an overall reduction in male fertility. Citing three studies, including a 1990 study by John McLachlan (of retracted Tulane study infamy), Skakkebaek concluded his study with, “Whether estrogens or compounds with estrogen-like activity (as proposed by some) or other environmental or endogenous factors damage testicular function remains to be determined.”(47)

By 1993, Skakkebaek had fully subscribed to the endocrine disruptor scare in an article in The Lancet:, “We argue that the increasing incidence of reproductive abnormalities in the human male may be related to increased estrogen exposure in utero, and identify mechanisms by which this exposure could occur.”(48)

Theo Colborn embraced Skakkebaek’s claims in “Our Stolen Future.” Although Colborn noted that Skakkebaek’s claim “is still meeting with a skeptical response in parts of the medical community,” she dismissed the skepticism by comparing it to “similar disbelief at the first news that a dramatic hole had developed in the Earth’s protective ozone layer over Antarctica…”(49)

State of California researcher Shanna Swan joined the sperm count fray in 1997 with her 1997 study in Environmental Health Perspectives that claimed, “This analysis demonstrates that the decline in sperm density reported by [Skakkebaek in 1992] is not likely to be an artifact of bias, confounding or statistical analysis.” Swan declined to address the “cause(s) of the decline.”(50)

Swann tried to tie the alleged decline in sperm count with exposure to pesticides in a 2003 Environmental Health Perspectives study. She reported lower sperm counts among sperm donors in rural, agricultural Columbia, Missouri versus donors in more urban areas like Los Angeles and New York City.(51)

Swann and Skakkebaek have been at it ever since, constantly claiming that sperm counts are declining and that endocrine disruptors might be responsible.

Toxicologist Stephen Safe has been skeptical of the claims of Skakkebaek and Swan. In 2012, Safe wrote, “The initial endocrine disruptor hypothesis which suggested a link between in utero exposures to estrogens and decreased sperm counts is not supported by most studies but is still championed by Skakkebeck and some of his co-workers…”(52)

Safe added, “The claims and controversies regarding EDCs have continued for almost 20 years and there are no signs of resolution. It is noteworthy that two preeminent reproductive biologists who have made highly significant contributions to this field have developed skepticism on the claimed effects for BPA… In a commentary, Sharpe, a coauthor of the initial endocrine disruptor hypothesis, clearly answered in the affirmative the title of his highlight ‘Is it time to end concerns over the estrogenic effects of BPA?’”

Sharpe was Skakkebaek’s co-author on the initial 1992 study.

References

- https://cen.acs.org/articles/92/i20/ENDOCRINE-DISRUPTORS.html

- https://www.forbes.com/forbes/1998/1116/6211146a.html#2f36f11b6012

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phytoestrogens

- https://www.forbes.com/forbes/1998/1116/6211146a.html#2f36f11b6012

- https://www.forbes.com/forbes/1998/1116/6211146a.html#2f36f11b6012

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1638151/pdf/envhper00307-0053.pdf

- Maugh T, Chemical carcinogens: how dangerous are low doses? Science 06 Oct 1978: Vol. 202, Issue 4363, pp. 37-41. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/202/4363/370.

- Ames B et al. Dietary Pesticides (99.99% all natural). Proc Natl Acad. Sci Vol. 87, pp.7777-7781, October 1990.

- Crump K et al. Estimates of the proportion of chemicals that were carcinogenic or anticarcinogenic in bioassays conducted by the National Toxicology Program. Environ Health Perspect 1999 Jan;107(1):83-8.

- https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/remembering-theo-colborn

- http://www.ourstolenfuture.com/Consensus/immuneauth.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theo_Colborn

- http://www.ourstolenfuture.com/Consensus/wingspreadimmune.htm

- Safe S. “Endocrine Disruptors: New Toxic Menace?” in Earth Report 2000 (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 192.

- https://www.nap.edu/catalog/6029/hormonally-active-agents-in-the-environment

- “This project was supported by Contract No. CX 824040-01-0 between the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Cooperative Agreement No. 1445-CA09-96-0027 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Biological Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior.” https://www.nap.edu/read/6029/chapter/1#ii

- Thomas KB and T Colborn. Organochlorine endocrine disruptors in human tissue. Pp. 365-394 in Chemically Induced Alterations in Sexual Development: The Wildlife/Human Connection. T Colborn and C Clement, eds. Princeton NJ: Princeton Scientific Publishing.

- Colborn T, FS vom Saal and AM Soto. Developmental effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Enviro Health Perspect 101(5):378-384 1993.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/23/opinion/l-new-studies-confirm-pesticide-cancer-link-858495.html

- Arnold SF et al. Synergistic activation of estrogen receptor with combinations of environmental chemicals. Science. 1996 Jun 7;272(5267): 1489-92.

- https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/endocrine-disruptor-screening-program-edsp-overview.

- From the H. Rept. 104-669 – FOOD QUALITY PROTECTION ACT OF 1996 (https://www.congress.gov/104/crpt/hrpt669/CRPT-104hrpt669-pt1.pdf):

“The Committee is aware of recent scientific reports indicating that some pesticides may imitate, enhance, or block the activity of hormones in humans and wildlife. For example, a linkage has been suggested between human exposure to chemicals that imitate estrogen and breast cancer. Since hormones govern fundamental bio- logical functions such as reproduction, growth, and metabolism in humans and other species, the Committee believes that it is important for EPA to obtain data about the potential hormone-disrupting effects of pesticides in order to make informed regulatory decisions under FIFRA.

The Committee notes that the Agency has commissioned a report from the National Research Council to examine the issue more closely and identify data gaps that exists in current testing requirements. The Committee has reviewed and considered this issue and has determined that the EPA currently has sufficient authority to request information related to such effects. The Committee recognizes there are efforts ongoing to design and implement research to objectively assess and characterize the risk of endocrine disruptors on human health and the environment. Therefore, the Committee expects the Agency, within 4 years of the date of enactment of this Act, to evaluate the need for and, if necessary, to use its existing authorities under sections 3 and 4 of FIFRA to establish standards for data requirements, to determine whether a pesticide can disrupt hormonal activity. Collection and analysis of data specified in EPA standards related to disruption of hormonal activity should not delay reregistration eligibility decisions for pesticides first registered before 1984.

- https://www.eenews.net/eenewspm/stories/1059948721/search?keyword=EPA+EDSP

- https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/endocrine-disruptor-screening-program-edsp-tier-1-assessments

- https://peerj.com/preprints/2527.pdf

- https://junkscience.com/1997/08/junk-science-its-the-law/

- McLachlan J. Science. 1997 Jul 25;277(5325):462-3.

- https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-02-003.html

- https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/pressctr/mtgs_wkshps/2000/lowdosepeerfinalrpt.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?p$l=Email&Mode=download&term=bisphenol%20a&dlid=timeline&filename=timeline.csv&bbid=NCID_1_54724179_130.14.22.215_9001_1528398674_1444908328_0MetA0_S_MegaStore_F_1&p$debugoutput=off

- https://www.sfgate.com/health/article/CALIFORNIA-Legislature-considers-bill-to-ban-2719099.php

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/45073/

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/56657/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2967230/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/14/world/americas/14bpa.html

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1059942043

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1059942580

- https://www.eenews.net/eenewspm/stories/1059954726

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1059967407

- https://www.newsday.com/news/health/suffolk-lawmakers-ban-receipts-with-bpa-1.4291337

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1060010213

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1060012108

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1060035955

- https://www.eenews.net/greenwire/stories/1060074753

- https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/120/12/ehp.1205330.pdf

- https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/results/areas/bpa/index.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1393072

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PII0140-6736(93)90953-E/abstract

- Our Stolen Future, 172-176.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470335/pdf/envhper00324-0076.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12676592

- http://www.asiaandro.com/news/upload/20130912-aja201287a.pdf